The second part of Revelation 2: 7 is a good example of why finding the subject of a sentence is important. For one thing, it is not always expressed separately in Greek, as we see below:

τῷ νικῶντι δώσω αὐτῷ φαγεῖν ἐκ τοῦ ξύλου τῆς ζωῆς, ὅ ἐστιν ἐν τῷ παραδείσῳ τοῦ θεοῦ.

to the victorious one I will give to him to eat from the tree of life, which is in the paradise of God

Since I have translated this more or less word for word, the English is awkward, but should be understandable.

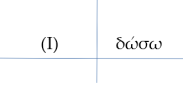

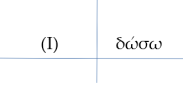

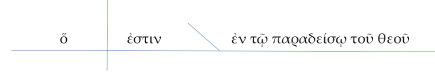

So where is the subject? The main verb is δώσω – ‘I will give’, and the subject is thus ‘I’, but not expressed with a separate Greek word. The basic framework of the sentence is:

(When a Greek subject is not separately expressed my habit is to put the English translation in parentheses on the subject line. This avoids leaving the space blank or filling in with a Greek word that isn’t found in the sentence.)

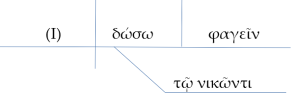

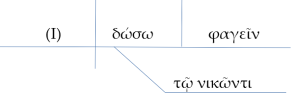

What is being given? In this case we can think of the infinitive φαγεῖν (‘to eat’) as the direct object of δώσω. Some English translations make this relationship clearer than others; the NIV, for example, reads ‘I will give the right to eat’. And who has been given this right? For the indirect object we must return to the beginning of the sentence: ‘τῷ νικῶντι’ (‘to the victorious one’).

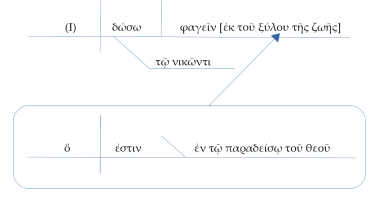

Here is the diagram:

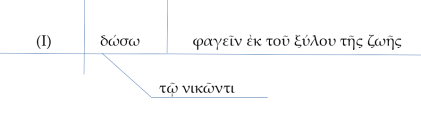

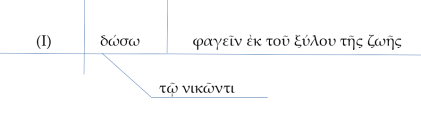

The rest of the sentence includes phrases which modify this basic structure. ‘From the tree of life’ answers the question ‘to eat what?’, and is a prepositional phrase modifying φαγεῖν. In my own studies (I don’t pretend this is approved diagramming procedure) I would simply add this to the direct object, as below:

Finally, let’s briefly consider what do with do with the phrase

ὅ ἐστιν ἐν τῷ παραδείσῳ τοῦ θεοῦ

which is in the paradise of God

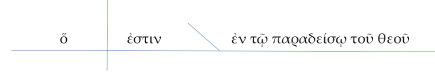

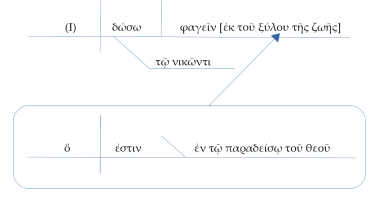

The part of the sentence has its own internal structure, something like this,

where the prepositional phrase ἐν τῷ παραδείσῳ τοῦ θεοῦ is linked (slanted line) as a description of the subject, in this case describing its location. The entire clause modifies τοῦ ξύλου τῆς ζωῆς, and here is a stab at a diagram of the sentence as a whole:

Once again, the purpose of diagramming a koine sentence is not to become enmeshed in detail, but to make the underlying grammatical structure more obvious, as an aid to understanding.

If you click on the menu icon above, i.e.:

you will see a list of permanent pages on this website. I’ve added a new page for conjugation tables, and will eventually include sub-pages for all verb conjugations. At the moment it includes only a sub-page for the present tense.

It is sometimes useful in predicting forms, or in working backwards from a given word to its lexical form, to know how Greek consonants combine.

For example:

(1) The perfect stem of the verb γράφω (‘I write’) is γεγραφ- .

(2) The first person singular ending for the perfect middle/passive is -μαι.

(3) When we combine the stem with the ending we get

γεγραφ μαι

but this combination (φ + μ) changes to ‘μμ’, thus the actual form is:

γέγραμμαι

Similarly, the combination of the stem γεγραφ- and the second person singular -σαι is γέγραψαι. Note that this is also why the future of γράφω becomes γράψω. (φ of the present stem plus the σ of the future endings).

The subject is complex, and may not be of interest for many readers. However, for those who like to delve into morphological details, here are some resources:

1. Machen and McCartney, New Testament Greek for Beginners, second edition. Pearson/Prentice-Hall, 2004,

See pp. 321-323. The charts here, in my opinion, are some of the clearest illustrations of these consonant combinations.

2. H. W. Smyth, Greek Grammar. Harvard University Press, 1920/1956.

See pg. 24 ff. This is the old classic of Greek grammar; it is still available on amazon, but readers should make every attempt to get the hardcover 1956 edition put out by Harvard UP. It is more expensive than newer paperback reprints, but anyone buying Smyth in the first place is a very serious student of Greek!

See especially #15 and following, although I believe there is a mistake in the table on ‘Attic Combinations’: φ + σ should combine to ψ, not ξ.

Below is a slightly adapted excerpt from the third Workbook.

“In koine Greek, as in classical Greek, verbs are traditionally assigned principal parts, a set of six basic forms (often designated by Roman numerals) from which all other forms of the verb can be derived. As an example, the principal parts of πιστεύω are as follows:

I πιστεύω present active indicative

II πιστεύσω future active indicative

III ἐπίστευσα aorist active indicative

IV πεπίστευκα perfect active indicative

V πεπίστευμαι perfect passive indicative

VI ἐπιστεύθην aorist passive indicative

Note the following:

1) The imperfect is a tense, but not a principal part, because the forms of the imperfect can be derived from principal part I, the present.

2) Similarly, the pluperfect is a tense, but not a principal part, because its forms can be derived from the perfect.

3) The present tense has only one principal part. All voices and moods of the present can be formed from principal part I: active, middle and passive; indicative and subjunctive, participles, infinitives, etc.

4) The future also appears to have only one principal part but, as we shall later see, the future passive is formed from principal part VI, a detail which is not at all obvious at first glance.

5) The aorist has two principal parts; III and VI. The aorist active and middle are formed from principal part III, but the aorist passive requires its own principal part, because it cannot be reliably derived from III.

6) Similarly, the perfect has two principal parts; IV and V. The perfect active and pluperfect active are formed from IV. The perfect middle/passive forms are derived from V.

* * *

In theory, all forms of a verb can be derived from its six principal parts. In practice, some derivations are trickier than others.”